I originally wrote this as an article for Black Diamond’s blog and then Ascent Magazine, but I wanted to go further in depth for the blog, so I’ve added a shit ton of photos and quite a bit more blabbering. These were some of the finest moments and conditions on one of the finest mountains, so maybe it’s worthwhile.

Alaska has been my ski destination of choice almost every spring for the past 13 seasons. The relative ease of access, generally deep dependable snowpack, wide variety of terrain and objectives, and affordability can’t be beat. I’ve camped and explored in 7 different ranges, skied off Denali, pioneered first descents in the Revelations and filmed steep spines in Haines and the Tordrillo’s for Powderwhore. The more visits I make the longer the list of things I’d like to ski grows. It’s not all sunshine and rainbows however. I’ve ended up tent-bound for 8 days with as many feet of snow falling on us. I’ve been stuck in Talkeetna in the rain for 9 day stretches where no planes flew in or out of the glaciers, I never even touched snow on that “ski vacation”. Skiing in Alaska is feast or famine touching the heights and depths, but the highs are very high and the lows are quickly forgotten with time. What I’ve learned is that you need to have a wide range of options, adapt, be flexible with plans—and most importantly—just keep showing up.

In May 2018, I returned to Alaska, this time with Teton legend (it only took him 2 years in the range to gain this status) and guide, Adam Fabrikant. We were casting a wide net in terms of our objectives, almost all of Alaska was in play.

A few buddies of ours had flown out of the mountains. I had breakfast with them and they told me about their trip and most memorable was their motto of “must be present to win”. I liked the double meaning of their motto a lot. First, like I said earlier you just have to physically show up to put yourself in position to “win”. Secondly, once you are in the mountains the main goal and requirement is to stay present in the moment, dealing with the thoughts and emotions and conditions at hand. Adam and I borrowed this motto for out trip.

After seeing the unsettled weather forecast across most of the state, we chose to fly into the Kahiltna base camp in the Alaska Range, which is the staging area for Denali and Sultana. Here, we could find plenty of good ski options at many different elevations and aspects to increase our chances of making turns down something that would fall into our slightly twisted definition of “interesting”. Our main objective became the 11,000 foot Archangel Ridge on Sultana, since we had both skied off of Denali and I don’t know of many other 11,000 foot runs that averages 40 degrees.

(Transportation indeed, from the green lush lowlands straight into the frozen white wonderland in an hour.)

On the way into the range we paid extra for a fly over of the Archangel ridge of Sultana. Upon inspection, the line was very icy and not holding snow, so we crossed it off the list.

(The north slopes of Sultana, hard to see in this image, but the upper half of the mountain had a certain sheen that didn’t bode well for ski edges)

(Aerial view of the ants marching towards the mighty Denali)

From the sky we caught a glimpse of the base of the Ramen Couloir on Begguya. The bottom of it was poking out of the clouds and surprisingly there wasn’t any avalanche debris or runnels which was a good sign. This rarely skied line quickly became the new object of our conversations and focus. Normally it would be too late in the year to consider this lower elevation south facing line, but May had been one hell of a snowy month and the storms had just now abated.

(With continued mixed weather in the forecast we set up camp near the landing strip.)

(Good to be back)

There are several small peaks right out of camp that looked like fun skiing as well as a good chance to get to know the snowpack. First off we headed into the clouds toward peak 12,200. Just as we were about to turn around the sky cleared enough to lure us further in. It was pretty also.

This line has a fair amount of glacial hazard hanging over it. If the clouds hadn’t been protecting it all morning we would not have attempted it. The temps were still cool, but we hurried up and out from underneath it.

(Putting in the booter with Billygoat plates and crampons on. We ended up using these plates on everything we hiked in AK. I have no affiliation with them, it’s just an awesome tool when encountering deep powder with the occasional firm stuff underneath.)

(Adam above camp and the clouds with Sultana in the background.)

The clouds came back in and the winds picked up as we got higher. We stopped short of the summit by a few hundred feet and grabbed a snack before descending.

(Happy to be out and moving around in the mountains!)

Turns down the ridge were powdery and once we went out onto the southerly aspect the snow was firm and trying to corn up.

It snowed 6-8 inches that evening and the next day it started trying to clear in the eve so we headed out for another ski. Mount Frances sits at 10,450 feet right above camp and it has a bunch of cool looking ski and climbing routes on it. With limited visibility we went for the east ridge so we could ascend and descend in safety with easy navigation.

It was a fun climb with some exposed ice, but mostly soft snow. Fortunately the sun came back out for most of our descent and the powder turns equally as good as the scenery.

(The mayor of powtown right at home with the freshly coated Begguya as a backdrop.)

We arrived back into camp around 11 p.m. One of the coolest things about this time of year is that it stays light almost all day. The late sun was bursting all over Begguya like a clear sign from the gods to go and ski it. This was the beginning of a short break in the weather in which we decided to try and sneak in a climb and ski of the Ramen route. We packed up 2 nights and 3 days worth of food and fuel.

We told a few folks of our plans and around 1 a.m. we slid quietly out of base camp and down the massive glacier while everyone around us slept.

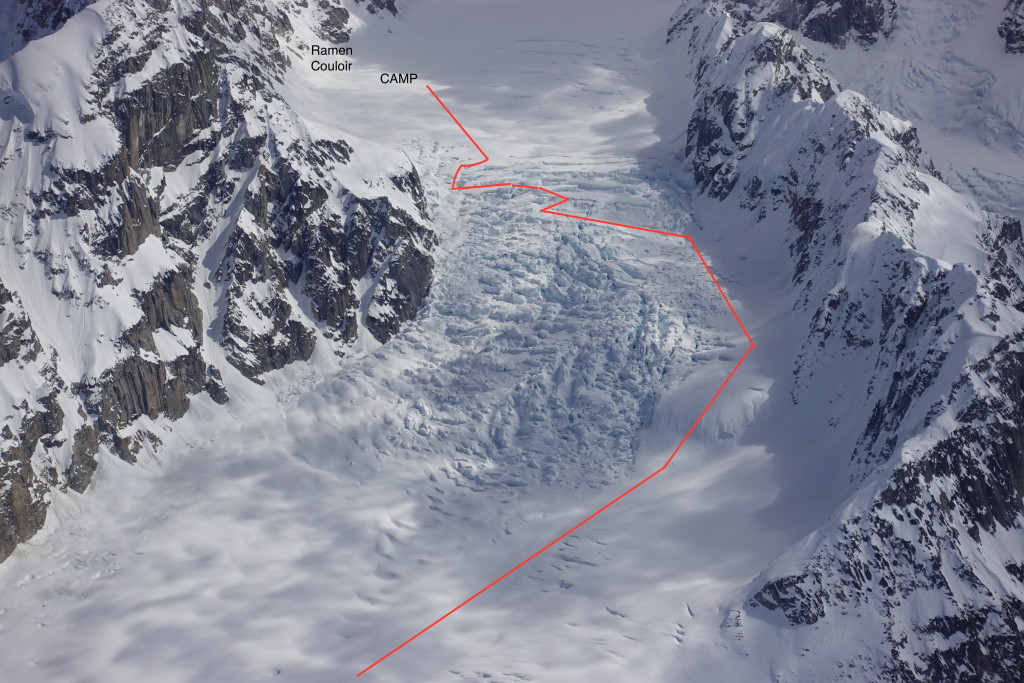

To get to the base of the couloir Adam and I traveled down the main Kahiltna glacier for several miles and hooked a left up the unnamed glacial branch. It probably doesn’t have a name because it sees so little traffic. It sees so little traffic because there are few people stupid enough to want to go up it. It requires guessing your way through a very intimidating and enormous Tim Burton-esque ice-fall.

Luckily we had taken some nice images from the flight in and we plotted a rough line that we hope would go without too much shenanigans.

If you’re going to do stupid things you’ve got to be smart about it, so we chose to navigate in the middle of the night when the frozen towers and bridges might stay put. Luckily, we chose well and only had to backtrack a few times and climb one short vertical section.

(Walking and weaving our way through in the wee hours.)

(Arriving six hours later in the upper basin with the enormous Ramen Couloir staring right back at us.)

(The upper section where the snow meets the ridge via a steep chute, or by traversing through and over some hanging seracs. Pick your poison.)

We set up a tent at around 8,000 feet, within a few hundred yards of the couloirs base and jumped into our bags to warm up and rest.

(The three sure signs of an expedition; puffy jackets, frosted beards and tent selfies.)

The sunny day was spent relaxing, hydrating, eating and staring up at the line. Our view went partly in and out of the clouds, but we caught full glimpses from time to time and it looked quite nice, filled in and free from much debris.

Ski mountaineering consists of skiing yes, but most of the time is actually spent in preparing and speculating. What will the snow be like? Where is the crux? How much time will it take? How much food should we bring? Should we bring a stove? How much water? What gear will we need? What layers? When do we start? This dialogue is a vital part of the process which usually helps alleviate concerns, but for some reason I got worked into an anxious state from these mental exercises. I was afraid of finding blue ice up there and then I started questioning my abilities and the spiral went downward and downward. I opened up to Adam about what was going on and he helped talk it out. I felt much better after that and was able to quiet the mind even though I wasn’t able to sleep much, just toss and turn waiting to get into action. I could have stayed silent and not dealt with it, but that’s not being honest or a good partner in my view (must be present to win).

At 14,573 in elevation, Begguya (Denali’s child, in its native tongue), or Mount Hunter (for old white colonialists), is the 3rd tallest peak in the Alaska Range and the 10th in the state. Of the three tallest, Begguya is considered the most difficult peak to climb and the hardest 14,000 foot peak in the good old USA. It only sees a handful of attempts and very few summits each winter. Most are via the steep and highly technical Moonflower Buttress, or the less difficult, but very long West Ridge. The mountain sees even less skier traffic and has only been descended by one route, the Ramen Couloir. In 2003, a crew with Lorne Glick and Andrew McLean, John Wheadon and Armond DuBuque pioneered this complex 8,500 foot route. Since then two other parties have succeeded on it. There have been a few unsuccessful attempts at other sides of the mountain, including one by Adam Fabrikant, Billy Haas and a top notch gang who worked on the East Ridge but were turned back by severe cornicing.

We started booting up the chute at 11 p.m. that evening and the ability to move dispersed my fear and turned all those question marks into exclamation points. The Ramen Couloir itself is a 3,300 foot, 50+ degree, south facing chute the gains the west ridge and follows it for another 3,000+ feet to the summit. We made good time taking turns breaking trail through the pre-frozen crust. Near the top we cut to our right through some large seracs and then up to gain the ridge. This was the steepest and most exposed part of the route by far, but the snow was firm and our crampons and axes gave us purchase and confidence enough to climb it unprotected or roped. It was nice passing through in the relative darkness and not getting to fully appreciate the exposure, that would come later on the descent.

I didn’t take many photos in the chute because it was dark and we were taking care of vertical business. Once we hit the ridge it was a different story, I had a hard time keeping moving, I just wanted to take pretty pictures like this one!

And this one!

The soft sunrise seemed like it lasted for four hours.

We tried to keep moving along the ridge with two difficulties, breaking trail in deep snow and not stopping every other step to take in the subtle light casting gently on the endless alpine all around and below us. I’m not sure I’ve had a more magical morning on any mountain in any range, ever.

Adam was moving well and faster than me, as always. He was cold and didn’t want to stop to refuel so we kept moving with him dragging me along taking pictures of his ass.

We popped into a few crevasses up to our waists, but they were shallow and small and skis have a nice way of catching you when your feet punch through The rope is a great piece of mind and insurance, we stayed tied in.

The ridge was mostly soft snow, we traveled with a mix of skinning and crampons w plates through a few steeper bulges and bumps. Then it opened up and flattened out onto the plateau. We finally took a break, but by then our water was frozen and we were too chilled to stay long.

(Taking a much needed break before the final summit face.)

The upper headwall was a foot or so of powder over ice to start and then just ice as it became steeper. We took turns running it out with a screw here and there, but the ice took good purchase with tools so we moved pretty quickly. Then it turned back to snow and Adam went back to work trail-breaking. I felt bad because I just couldn’t muster much that day and Adam ended up breaking almost all the trail along the west ridge after we had split up the work 50/50 in the couloir. That wasn’t a good feeling, not to be able to show up and do my part.

(final steps to the summit)

(Sun’s out, guns out.)

It was a great feeling finally arriving on the summit. I wonder how rare a sunny day with no wind on the top of Begguya is. It felt special, that warm welcome. We sat exhausted and in awe at where we were. Denali had some clouds covering the summit, but everywhere else was clear.

(Denali with a cloud cap.)

(Looking down on Mount Frances with a red line drawn down our ski descent)

Rugged white mountains……..everywhere.

(The view of Mount Huntington and the Moose’s Tooth to the east.)

(Looking down on Peak 12,200 with a red line drawn down our ski descent)

Real men talk about feelings and we tried to put words around the unspeakable, but they all felt small and inadequate, like us. So mostly we just sat and enjoyed truly being there. It felt special, spiritual even—whatever that means—maybe I was just hungry.

The sun was warming us nicely, but that meant it was also heating up our south facing couloir well below us. I didn’t want to move from our bliss, but after an hour it was time. One of the best parts about skiing, is the actual skiing. It felt amazing to click into bindings and have that confidence that’s attached with this simple act. Instead of trudging back down, we now got to slide and glide in a fraction of time what had taken us 10 hours to climb.

(Top of the world turns)

The initial skiing on the mellow summit ridge was great. The steep face required some roped shenanigans to get down and off of it. We should have just put on crampons and rappelled, but we tried to keep skis on for it, but after getting out onto it, our edges wouldn’t bite. It ended up taking more time than we wanted and became a bit of a cluster-fuck. We quickly got our shit together and got off the slope. We cleared our frustrations like a good team does (must be present to win) and moved onto powder skiing. From there it was smooth, soft sailing down the ridge. We stuck close to our uphill track so we could avoid roping up and falling into any new unseen crevasses.

(Does it get any better than this?)

The top of the Ramen opened up before us and Adam asked if I wanted to give it the first go. The fear I had felt about this section was totally gone and I was excited to lay edge to frozen water. I slowly worked in while feeling it out with tight controlled hop turns as it rolled to well over 50 degrees. It was perfect corn. At this steepness of pitch, turns are effortless. The edges release easy and the ski naturally finds it’s way around as it slices perfectly into the soft snow and prevents you from falling to your death. Maybe this was being on the edge that we were seeking, that fine balance of being in precise control during a precarious situation.

No place to fuck up as we worked our variation through the seracs and into the main chute. The steepness didn’t let up much and we worked smooth patches of corn in between rock islands and jumbled piles of frozen debris.

Steep skiing can be horrifying in poor conditions and heavenly under the right circumstances. This was perfection.

Adam shot ahead and I slowed down to milk the run, I didn’t want it to end. The steep angle continued all the way to the glacier and we both commented that it might be the most consistently steep run we’ve ever skied, over 3,000 feet that didn’t dip below 45 degrees.

We dried out our gear, fed and watered the body as we hid from the sun. We needed to wait for the temps to drop before we could exit through the icefall.

Adam’s toes were bothering him, we thought it was some light bruising from the front pointing, or frost nip.

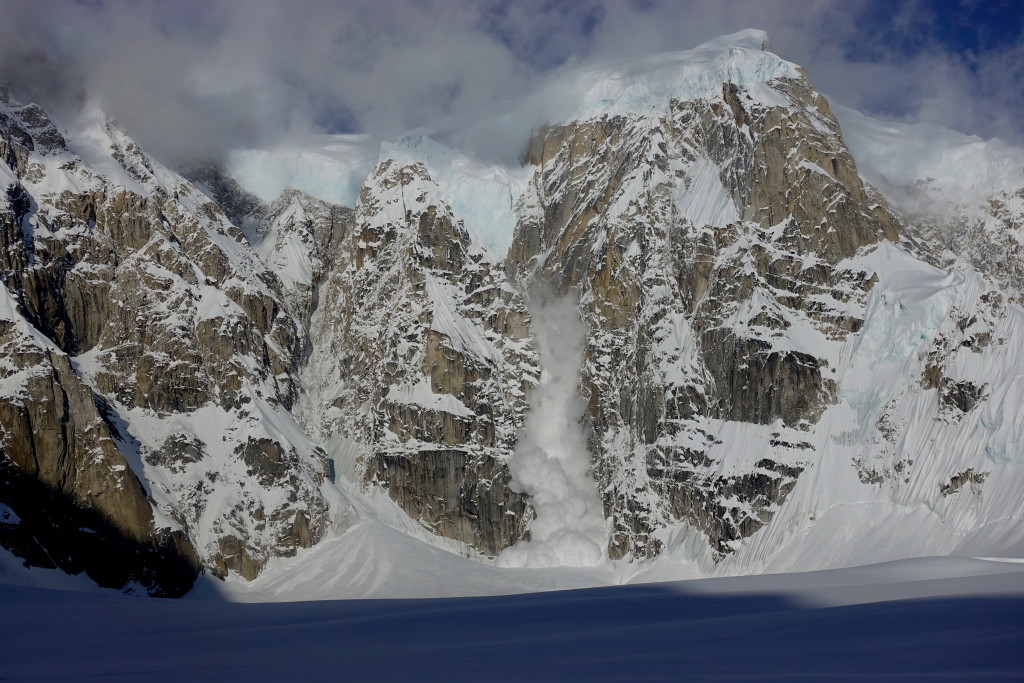

As we waited the mountains started unleashing large avalanches for our entertainment pleasure including some big wet slides right down the Ramen. Our timing had been incredible!

(The steep cirque put on a show.)

Our route back through the icefall was expedited by following our tracks and wands. A large block had fallen off and covered our tracks in one section and we were glad to get through safely and back out onto the flat wide open Kahiltna glacier.

That night we rolled back into Kahiltna base-camp late, we slept hard well into the next day. Adam had developed some blisters on his toes that seemed to be from frostbite. We consulted the rangers and they confirmed that to be the case. Despite Adam’s ever strong desire to keep skiing, we convinced him the best call was to return to town and take care of his feet before more damage was done. He was scheduled to guide a group on Denali in eight days and he’d need all the time for his toes to recover as he could get. He reluctantly agreed. We hadn’t been out that long, but we had skied three excellent lines and now it was time to leave the mountains.

(Adam back in Talkeetna getting his toes looked after.)

I’d like to think our many years of experience, good preparation, great communication and team dynamics allowed us to pull off a great line in one of the most incredible ranges on the planet. But, the truth is that mostly we got lucky with weather and conditions. After we flew out of the Alaska Range there was a short continued spell of good weather, but then significant snowfall returned to the range and thwarted most parties and their plans. There were probably only a handful of days where summiting Begguya was even possible that season, as far as we know we were the only team to do so.

Adam’s toes did suffer some minor frostbite, but he went back onto the mountain to guide and continues to crush the big lines.

I’ll be back to AK this spring, maybe just to sit in the coffee shop in Talkeetna watching it rain, or perhaps to be tent bound in a snowstorm, or maybe I’ll get to stand on top of something tall and ski down it, only one way to find out.

A huge thanks to Black Diamond, Julbo and Scarpa for providing the best gear around and for the awesome continued support.

Привет дамы и господа!

Наша фирма занимается свыше 10 лет изготовлением памятников из гранита в городе Минске.Основные направления и виды нашей деятельности:

1)памятники из гранита

2)изготовление памятников

3)ограда на кладбище

4)благоустройство могил

5)благоустройство захоронений

Всегда рады помочь Вам!С уважением, PRIME GRANIT

http://www.giveupalready.com/member.php?199366-Zelenajeb

http://aquamarineserver.com/discuz/home.php?mod=space&uid=12133

http://www.space-prod.com/index/8-19357

http://games.gcup.ru/index/8-28866

https://webraovat.com/author/zelenavza/

Привет господа!

Наша организация занимается свыше 10 лет изготовлением памятников из гранита в городе Минске.Основные направления и виды нашей деятельности:

1)памятники из гранита

2)изготовление памятников

3)ограда на кладбище

4)благоустройство могил

5)благоустройство захоронений

Всегда рады помочь Вам!С уважением, PRIME GRANIT

http://ru.pravoteka24.com/user/Zelenaore/

http://seowitkom.ru/index/8-43435

http://montazh.ua/user/Zelenagwc/

https://ochakov-segodnya.com.ua/user/bradacahvs5533/

http://peugeot-207-club.ru/forum/member.php?u=259003

Приветствую Вас товарищи!

Наша контора занимается свыше 10 лет изготовлением памятников из гранита в городе Минске.Основные направления и виды нашей деятельности:

1)памятники из гранита

2)изготовление памятников

3)ограда на кладбище

4)благоустройство могил

5)благоустройство захоронений

Всегда рады помочь Вам!С уважением, PRIME GRANIT

https://btcoinz.com/forum/profile.php?id=1141711

http://aikidoyukishudokan.com/forum/member.php?29465-Zelenaspu

http://mp3uz.uz/user/Zelenaydk/

http://chunboshi.cn/home.php?mod=space&uid=204545

http://www.hongfengzhineng.com/home.php?mod=space&uid=265877

So good. Thanks for sharing, sounds like an all-time trip!

Thank you Brad! All-time indeed, hope to get to do it again soon. 😉

Bad ASS. I love these trip reports.

Thanks a ton! I enjoy sharing and it’s fun to hear folks enjoy it.

This shit is the shit

Thanks for dropping by and taking the time.